I gave a talk the other evening at an Atlantic Salmon Trust event at the Curzon cinema in Mayfair. An eventide celebration, presenting the projects and progress of the Trusts’ work over the last year. There is profound optimism that we can help the now IUCN-listed endangered Atlantic salmon. With each new piece of data and evidence gathered, we increasingly ‘join the dots’ to understand how we give them the cold, clean water they require. However, the scale of the task ahead is daunting, and not to be underestimated when you consider we are moving at pace from what would now be considered tinkering around the edges to the realisation we need to encompass complete catchments. My piece was about river restoration on the river Dee in Aberdeenshire, which I will talk about in a minute, but first, I wanted everyone to understand how important this is for me.

I have fished the Dee continually (apart from one year due to Covid) for over 30 years with the same bunch of mates, and for me, helping Atlantic salmon is personal. It is so much more than just fishing.

For years, ‘ my week on the Dee’ has grown in family folklore as my downtime, my brain holiday, and my stepping off this world for a few days, all of which make me a better person. What we discuss in the fishing hut is ‘Mortimer and Whitehouse’ on steroids.

We know every stone and riffle on the water, yet things have changed.

Below my feet, eels would always wriggle away from you, and just upstream, you would step carefully over the pearl mussels – all sadly gone

This is the same pool at night. Fishing for sea trout immerses you in nature like no other sport. Your key senses of taste, smell, sight, and hearing are all relegated to the back of your brain; everything is focused now on touch and feel

We love this place, and we would not be proper fishermen if we were not also naturalists who care about the world around us.

But here is a sobering fact: excuse the pun

In the 1980s, during our week, we would drink around 30 bottles of wine and catch around 30 fish. Last year, we still drank around 30 bottles of wine but caught one fish. So, for the evidence-based data scientists among you, a ratio of one bottle of wine to one salmon has now dropped to a ratio of 30 to 1.

Long days and nights. People wrongly believe we are on holiday!

At the beginning of this year, the River Dee Trust, the Dee District Salmon Fishery Board, and the Atlantic Salmon Trust formed a partnership in the face of declining salmon returns, particularly the spring run, hence the name

I wanted to be a part of that work to help restore the river I love.

Why the focus on spring fish? The Dee is famous for its ‘springers,’ but the spring run catch has declined by around 80% in the last 50 years, and it is these populations that the program looks to help.

These fish predominate in the upper parts of the catchment, so the partnership is looking at the catchment upstream of Aboyne.

Increasingly, these are the parts of the system that are under the most pressure from climate change.

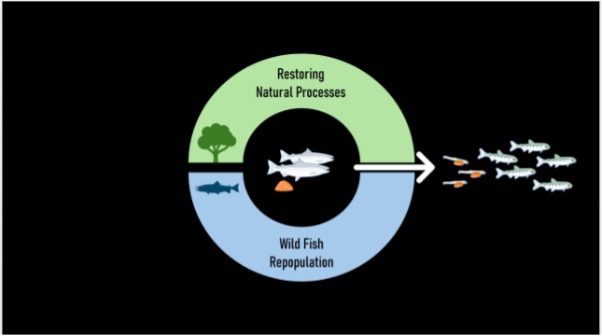

The first part of this strategy involves restoring natural processes in the river and surrounding landscape in these upper tributaries—the second half concerns wild fish repopulation, which I’ll discuss later.

Some key facts about how the environment has changed in the last few decades:

In 2023, 60% of the upper Dee catchment monitoring sites exceeded temperatures that cause thermal stress to young salmon. In the River Clunie, which meets the Dee at Braemar, water temperatures above 28C have been recorded in recent years.

Changes in weather patterns and frequent winter storms are also affecting the stability of the riverbed and spawning gravels.

A study carried out in 2023 found that only 10% of the river substrate is in a stable condition, compared to 50% in 2010.

Therefore, the first part of the programme is focused on actions to improve stability, slow the flow of water off the land, and protect against rising temperatures.

This strategy element focuses on creating a patchwork of native riverside woodland, restoring peatland and wetlands, and re-naturalising the river channels to:

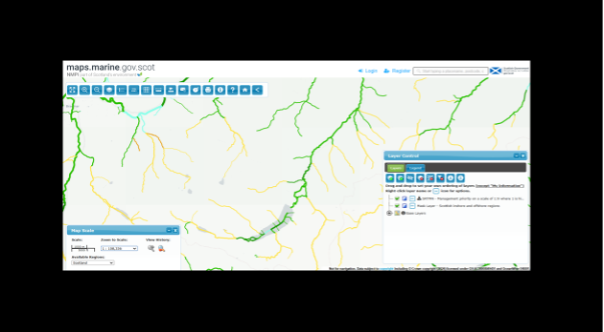

Marine Scotland has now measured the river catchment to individual burns by temperature risk.

Remember, the burns heat up, sending an invisible, insidious thermal pollution downstream. What happens high up in the catchment also affects down below.

Salmon become stressed, stop feeding at 23C, and die at 33C.

The optimum temperature for feeding and gaining the condition they need to survive best at sea is around 16C, so anything above that means their feeding and growth are slower and poorer.

These maps allow pinpoint accuracy to help prioritise where we should bring shade, with ideally a patchy woodland of mixed species connected along the river banks.

The colour legend is on a scale of 1-8 with 8 being the coldest. The yellow and amber you see here are down at 3 & 4.

This is an absolute game changer since it allows us to focus where we get the greatest bang for the buck in creating riverside shade.

Here is an example of newly planted tree cover on the Dee. It is patchy and native—this is not a row of Sitka spruce.

In recent years, the River Dee team has been doing incredible work on several upper catchment tributaries. If you drive over the top from Glen Shee to Braemar, you can now see these trees growing proud from the deer and sheep protection along the river Clunie.

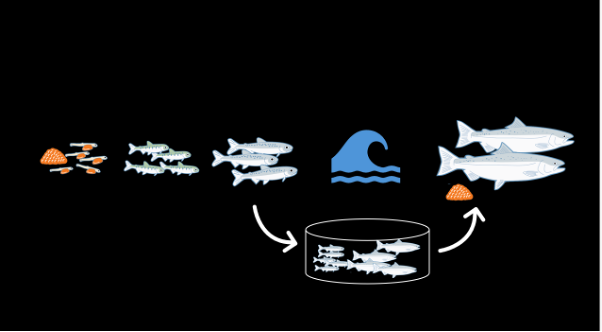

However, habitat improvement takes time, so we are helping nature with something called smolt-to-adult supplementation.

A helping hand during the most dangerous phase of their lives.

In some burns, the returning hen fish to spawn has reduced to a now critical level.

For example, the Girnock saw only two hens last year, a reduction from over 20 only five years ago and as many as 150 in the 1960s.

This calls for drastic intervention to prevent the loss of the individual genetics of these upper catchment tributaries. So, this year, we’ve been piloting this technique on the River Muick. The Muick has also seen a drastic reduction in returning spawners in recent years.

This is not a hatchery. We know that wild-hatched fish survive best over the course of their lifecycle, so the focus here is on assisting wild spawning and wild-hatched juveniles.

We now know that to increase smolt survival, fat-fit smolts need to run downstream, which is why we need to improve the habitat. They also suffer high mortality during the marine transition, and ultimately, fewer fish are returning as adults.

So, while we re-naturalise the habitat, we are capturing smolts and growing them in a tank maintained by Stirling University to safeguard them from this critical, dangerous phase of their lives.

We will then return them next autumn as mature adults to the exact spot where we captured them as smolts. Our aim is to provide an immediate boost to the number of adult salmon spawning in the area.

We captured 87 smolts in the spring for the programme, and we’re pleased to report that losses have been minimal. 82 are still in our care.

We captured smolts on the downstream migration back in May.

There is a parallel here on head-starting curlew chicks.

Curlew’s struggle to raise enough chicks, primarily due to the predation of nests and chicks, plus modern silage cropping.

We take eggs from ‘at risk’ nests, such as those on RAF airfields, and raise them in captivity before releasing them as adults. This also safeguards them through the most dangerous phase of their lives.

Back in May, the smolts were around 11cm. Now 6 months later, they are over 40cm.

Back in May, the smolts were around 11cm. Now 6 months later, they are over 40cm

In the wild, we might expect 1 or 2 of our 87 fish to return from the sea as adults to spawn, so if we can increase that number substantially, this could be a huge help to the natural spawning in the area.

This is a highly innovative approach, and we’re learning as we go. In terms of saltwater closed containment growth and release, it’s never been done quite like this in the UK before. We’re excited to see how these fish fare when released back into the river to spawn.

I have written before about Large Woody Structures (LWS)

But habitat work is already starting to show potential. I took this picture only two weeks ago, and it shows salmon redds on the river Muick next to one of the LWS structures put in by Lorraine Hawkins and Edwin Third of the river Dee trust. The river has carved out a little bay here around the woody structure, creating the perfect spawning environment

As we approached the salmon effortlessly drifted out of sight under the wood

And here is the same structure back in the summer showing salmon using the woody structure.

So, It’s personal, there is a programme and there is Hope

Finally, don’t forget Curlew’s need for open expanses away from trees and predators – Always the right trees in the right places.