Before you fill your garden with anything else, start with these six unsung heroes. Newly emerged bumblebee queens need an early energy hit—and vital supplies for their new broods. Make every plant count.

As you drift through the garden centre, the colours call out like sweets behind glass—irresistible, fleeting. It’s too easy to fall for the instant charm of blooms already peaked, a takeaway for the eyes—here today, gone tomorrow. Some wear the “bee-friendly” badge yet offer little when bees first wake and need it most. This spring, plant with purpose. Choose flowers that truly nourish. And as for fruitless ornamentals—why settle for show alone? A tree that feeds bees and bears fruit gives much more in return.

So here are my top six bee-friendly plants, carefully chosen to give the most significant boost in spring and early summer (from February to May) when pollinators need them most. For the best results, plant them in sheltered spots that catch the morning sun, offering warmth and nectar just as the bees start their day.

The magnificent Six

Crocus (but choose the right ones!)

Crocuses are among the best early-spring plants for bees, especially bumblebee queens emerging from hibernation. However, not all species are equally helpful. You want early-flowering species, ideally orange or purple, and nectar-rich.

One of the earliest to flower—often by late February—is Crocus tommasinianus or Crocus vernus, both open-faced varieties that serve their pollen generously. I grow them on a south-facing grassy slope I call my crocus bank. It’s the first place I look each spring to catch the emerging bumblebees.

Avoid the large, overbred double varieties. They have less pollen and are often harder for the bees to access.

The bee shown here with the orange tail and size indicates an early bumble bee (Bombus Pratorum)

Dwarf willow, Salix herbacea

Pussy Willow (Salix species)

Pussy willow is one of the year’s first quiet miracles—its soft, silken catkins catching the light before most trees have even stirred. This usually refers to the male catkins of Salix Caprea (goat willow) and Salix cinerea (Grey willow), which may be the only flowers available if the weather is poor. Therefore, when planting, you must choose male trees (with the yellow pollen-rich catkins). Female trees bear greenish catkins and don’t provide the same benefit.

Flowering from late winter into early spring, its golden catkins are rich in nectar and pollen, offering a vital lifeline to queen bumblebees waking from hibernation. But it’s not just bees—recently arrived chiffchaffs and willow warblers also depend on this early bounty. Planted in a sunny, sheltered spot, pussy willow becomes a beacon for the season’s first stirrings of life. The picture shown here is the dwarf variety in Iceland, where it was the very first plant of the year to stir.

Bumblebee on Purple Flower pulmonaria flowers

Pulmonaria (Lungwort)

My next bee-friendly plant is lungwort (Pulmonaria). This shade-tolerant plant, with its spotted leaves and two-toned flowers, is an early buffet for long-tongued bees and dark-edged flies. This year we had the Common carder bee, the Early bumblebee. Buff-tailed bumble bee and White-tailed bumble bee all feeding on lungwort as it fills a vital gap between the crocus and pussy willow before the bulk of the spring flowers. The picture is of another early bumblebee.

Bee collecting nectar from white flowers with wings visible

White Dead-nettle (Lamium album)

Often dismissed as a weed, the white dead-nettle (Lamium album) is a quiet hero of spring. Flowering early and generously, it offers nectar from late March to May. Unlike its stinging cousin, it’s easy to recognise and even easier to lift and replant—its shallow roots make it a gentle guest in any garden. I let it grow wherever it chooses—not just for the bees, but for its delicate white flowers, and as a reminder of spring. By summer, it retreats quietly back into the soil.

You are unlikely to find this in the garden centre, so treasure it if it grows in your garden. It is a plant of hedgerows and shady spots, perfect for wild places in the garden, but I find it equally at home in an herbaceous border. The white hooded blooms are specially shaped for long-tongued bumblebees like white-tailed bees. Even on cold spring days, they produce a reliable nectar supply.

The bee shown is a common carder bumblebee – one of the ginger-tailed varieties.

Comfrey (Symphytum officinale)

Comfrey, especially the early-blooming varieties, is a powerhouse for bumblebees with its tubular blooms. A very easy plant to grow from any snapped off piece of its thick but weak tap roots – I let it grow wherever it pleases for bees, if not bothering other plants. I then cut down the old flower stems to add to the compost heaps.

A bumblebee in a garden against a green background.

Borage (a little later) Borago Officinalis

Though not strictly ” spring,” borage kicks in soon after and flowers for months. Bees love it, and I let it self-seed and come up each year across the vegetable garden. Apart from the nectar, the two-tone blue and mauve/pink make them a very visual flower for bees to identify. And then, of course, you can pick the flowers for drinks or to colour your salads.

Identification

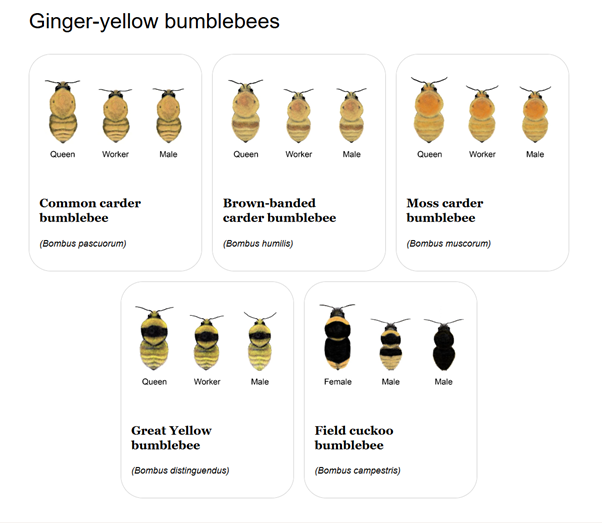

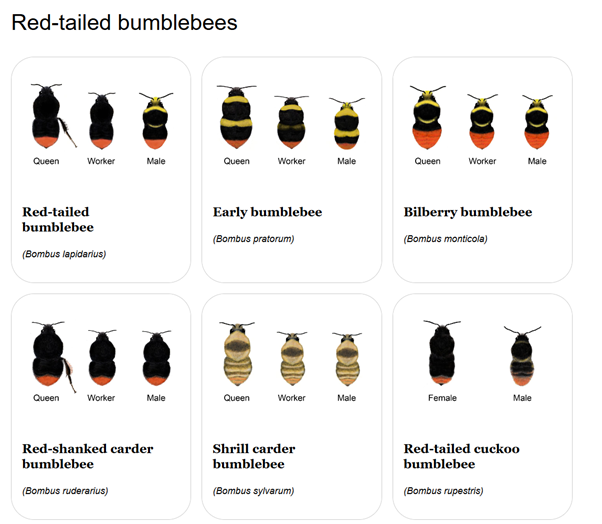

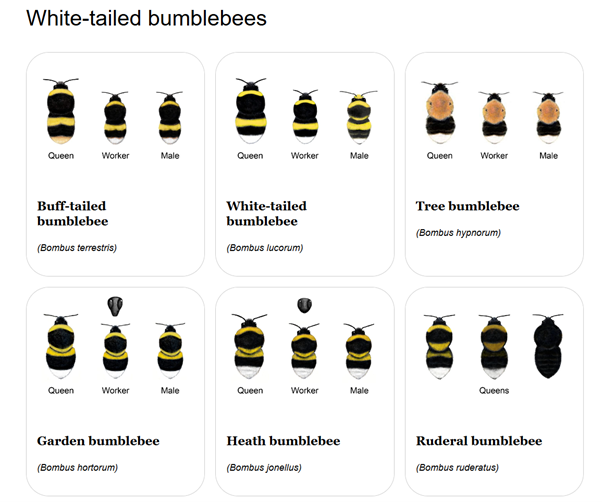

Now you can feel pleased by helping bumblebees in the spring, it’s time for the fun stuff—identification. Many early bumblebees look pretty similar, so a simple tip is first to consider the colour of the tail. This is how the Bumblebee Conservation Trust produced these ID charts, split into three tail colours: White, Red, and Ginger. More information can be found at www.bumbebeeconservation.org

Nesting

Unlike honeybees, bumblebees don’t build hives in the traditional sense. Instead, they create a loose, organic structure of wax cups—some cradling a single egg, others filled with nectar to feed the growing colony. Their nests are improvised, shaped by what’s available: a hollow in a dry-stone wall, a quiet cavity beneath a shed, or a tussock of grass left to grow wild. This adaptability—and their gentle, unassuming presence—makes bumblebees such quietly remarkable nesters.

To help them find safe nesting spots, I place upturned clay flowerpots in sheltered corners, out of direct sunlight. Inside, I tuck a smaller pot to create a snug, protected chamber, then line it with moss and dried grass. The ideal finishing touch is an old mouse nest—bees rely heavily on scent when choosing a home. Those queen bumblebees zig-zagging low over the lawn in early spring are house-hunting, often drawn to the earthy comfort of a former occupant’s dwelling—or, as in the case of Beatrix Potter’s Mrs Tittlemouse, a not-so-empty house, just right for raising a brood.

Flowers and nectar, shelter and safe nesting homes – you can do it!

In return, you’ll hear that wonderful low buzz of the larger bumblebees and the lighter, higher hum of carder bees. With luck, you’ll also notice improved pollination—and perhaps, more meaningfully, a quiet sense that you’ve come to understand more of the world around you.